But, Like, What Are You?

How a trip to Spain caused a momentary (yet lifelong) ethnic identity crisis.

It starts simply, with a “hola” from a friendly face across the counter of a Madrid clothing store selling discounted attire that you’re probably too old to be wearing. You hand her the knock-off white Converse style tennies that you fully intend to put on the minute you're outside because your feet are aching and blistering, and you only packed fucking sandals. An amateur move for someone who travels as much but you misjudged how out of shape you were and how acclimated you’ve become to sitting at a desk all day.

You hesitate because you know the minute you start speaking, you’re going to disappoint her. So, you mumbly reply, “Hola” and immediately follow with “No Habla Español.”

You worry that you sound like a complete idiot and wonder if she’s judging your godawful pronunciation that sounds like a step up from reading the Taco Bell menu. You fear you’re the Three Amigos version of her. Your ancestors would be so disappointed.

Her smile is now slowly transforming into a half-sneer. You recognize the question wash across her face like so many before her: what are you? You pay the woman, take your shoes, and maneuver around the racks of 90s retro socks and neon spandex to the exit door when you’re suddenly stopped by a saleswoman.

She is talking faster than you can follow and you’re pretty sure it's the Catalan language and not Spanish, but you know by the flyer that she’s shoved into your face that she’s asking if you want to apply for a store credit card.

“Sorry, hablo English…” you cringingly reply.

The saleswoman takes a small step back, looking you up and down, holding the flyer close to her chest with the most disappointed and confused expression on her face. “Oh, yes, this is not for tourists. Sorry, I thought you were from here.”

Here…

The word stings. You’re not from here.

You do not belong here despite your ancestral heritage.

You’re a foreigner.

An outcast.

Before you can conjure a reply or a manner of nonchalance, she walks away from you to the next credit card victim and an emptiness expands in your lungs. Something you haven’t felt in a very long time.

Aesthetically, I can fit in just about anywhere. When I moved to NYC at 21, everyone thought I belonged to them: the Greeks, the Armenians, the Puerto Ricans, and the Russians. My olive skin, large eyes, bushy eyebrows, and dark hair helped me navigate new neighborhoods as if I had always lived there. I was quickly welcomed into groups and families on the street or in delicatessens: “Oh, you have to meet my brother, Tony, he could use a beautiful Italian girl like you!” It didn’t matter that I didn’t speak another language because everyone understood the power and dismantling of assimilation in America. I was one of many swimming in a pool of uncertainty, occasionally drowning in the need for communal acceptance.

There have been many places that I have traveled to where I fit in. Where my gawk-free, quick stride on city streets is not interrupted by vendors wanting to sell me the same keychain as their neighbors (for significantly less), or when I’m approached by a local asking for help and shock washes over their face as they realize that I’m not (insert ethnicity/nationality). And that's the thing, I look like I could belong to anyone, anywhere, until I open my mouth.

The minute I speak in a foreign country, I am found out. My American drawl feels like a fine wine label wrapped around a Corona bottle. The air of sophistication I carry is immediately dismantled when I struggle to pick up a new language and my go-to words are purdy and fuck. I’m like a fancy Elmer Fud, shaped by rural Western Colorado, hoping that my smile won’t piss off a local because I’m just another “chipper tourist.”

I can usually brush it off: the unwelcome stares, the eye rolls, and obvious frustration when someone must speak to me, the American. I know we’re all categorized the same: obnoxious, loud, uncultured, and inconsiderate. I know I have to try that much harder to show that I am genuinely eager to immerse myself in the culture, but it wasn’t until I spent time abroad that I started to feel shame while traveling.

In the Summer of 2022, I was thrilled to visit Spain on a short detour before I headed to Turkey and Finland for a two-month writing adventure. My goal was to spend nine days in three different regions, beginning my trip in the country's capital city of Madrid. Then, from there, I would take the train north to the beautiful Basque region of San Sebastian where my cousin Courtney and her family lived, and finally southeast to the architectural wonder of Barcelona in the Catalonia region. I was excited to walk on the soil of my ancestors. Anticipating that maybe, just maybe, I would feel a sense of home there. A soul-like connection to the terrain and the people, but I didn’t. The country is vast and beautiful, very awe-inspiring but being there, as I quickly realized, made me feel like the White Girl being picked on during middle school recess all over again.

Half of my DNA is comprised of Indigenous Mexican/Native American and Spanish. Many of my maternal relatives speak Spanish but here I am with my limited vocabulary of sí, baño, comida de pollo, and a few choice curse words that everyone should learn from their Spanish-speaking friends, so you know when people are talking shit (mierda) about you. These are the cultures I grew up with and the ones I feel the closest and often the most distant to.

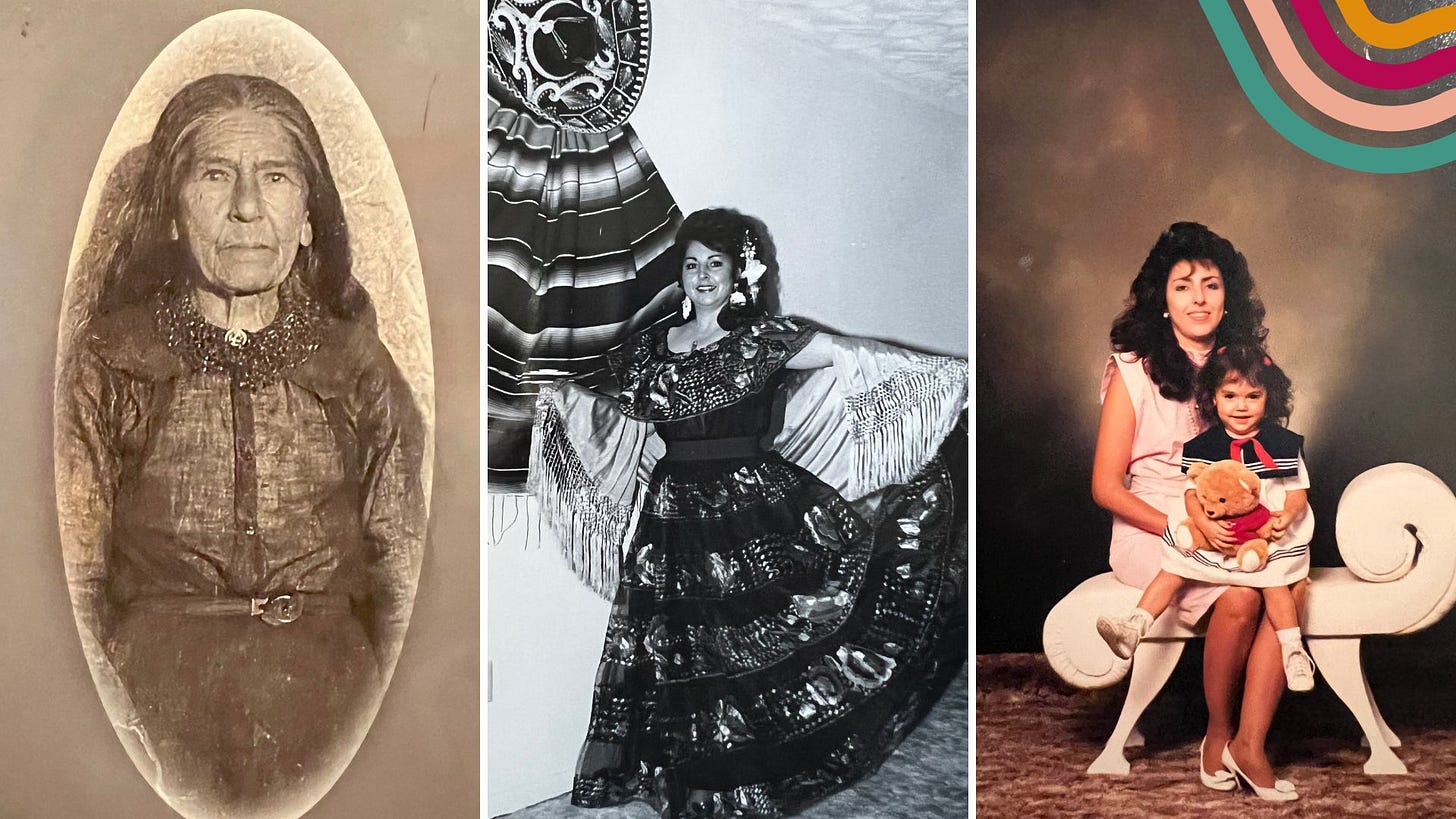

I spent most of my childhood with my maternal grandparents. Their home was filled with simplicity, laughter, and second helpings of dinner. My home was an unpredictable battleground. My grandmother, with whom I have always been close, introduced me to our eclectic heritage. Her passion and admiration for our culture ignited an incense of familiarity that made my soul dance. With her, there never was any question; of who or what I was. I just was.

In the early 90s, she was a DJ for the local radio station that played a variety of Mexican, Latin, and Spanish tunes on Sundays. I often joined her sessions and if I was lucky, she would let me read the weather report. In English. For over a decade, she owned a successful Spanish Dance Hall that frequently brought in bands from Mexico and Spain and was even a singer in a local English/Spanish band. She was on the planning committee for the Ute Council Tree Powwow and was previously involved with our Catholic Church in multiple capacities. A true force to be reckoned with, then and now.

My great admiration for my grandmother was also shared with many in the community who knew of her or heard about her through these activities. And lucky me, many of the kids knew of her too. It didn’t take long until many of my peers began to berate me during school: “Why don’t you speak Spanish like your grandma?” Often this was followed with some nonsense about being a “stupid lil’ gringa” or how I wished I was like them, but my skin was “white as snow.”

For a very brief period, in the sixth grade, I hung out with a small group of Hispanic and Latino girls. They were, for the most part, kind to me but loved to play a game where they would share secrets in Spanish and then make me guess what they said. I sucked at it but my witty answers often induced laughter.

The girls had an Us vs Them mentality that I’m sure was passed down by their siblings. I didn’t quite understand the concept, well, until it was too late. Like, when I decided to eat lunch one day with some of my Caucasian friends and was later threatened for “leaving the gang.” I missed a few days of school in fear of their retaliation because they were “going to beat my ass.”

I never hung out with them again.

The other half of my DNA is made up of 20% Italian, 15% Scottish, and a collection of Western European descent: Irish, English, and Belgian. My paternal grandfather, whose father migrated to the US from Italy through Ellis Island in the early 20th Century, has no contact with his family besides a sister in Tucson. I don’t communicate with my paternal grandmother and most of my paternal relatives due to whatever drama existed before I was born. Despite this separation, it was in my teen years that I found comfort in my Italian last name. The Caucasian kids never harassed me for not being White enough or that I only spoke one language. I felt safe with them, unburdened, and it was easier to just go along with what everyone had already assumed by my last name: that I was just Italian.

This method worked for a while but the older I became, the more I struggled with my identity and how others perceived me. My frustration often came out in hilarious ways. Like the time I was driving around with my bestie, Betsy, and she called me a White girl and I yelled back, “I am not White! My grandma makes tortillas from scratch!” We still laugh about this.

Through the years, I’ve struggled immensely with my heritage & culture, and ethnicity. The American government has probably, thoroughly, enjoyed reading any legal documents that have asked me to describe my race and ethnicity, considering that I have continually changed my answers, many times, in my adult life. Part of the problem is that I don’t know what to put. Do I only check White, or do I check White, Hispanic, and Native American? Does it make more sense to just check ‘more than one?’ Is this a numbers situation, like the race and ethnicity with the most percentage wins? Why does it feel like I’m the only one confused about what the parameters of an acceptable answer are for someone like me, especially when the 2020 US Census found that 10.2% (33.8 million) of the US population identifies as multiracial/ethnic? A huge jump from the ‘9 million people in 2010 who identified as multiracial - a 276% increase.’ (Jones)

Other people have also been confused about what I am, which isn’t the most comfortable thing to deal with when you’re a child. Especially, when the parents of your friends stare at you and talk about your “exotic features” or when they flat-out ask you, “What are you?” And you’ve never been educated on how to answer or what the question even means. You just know that it makes you feel different.

I still get the question, “But, like, what are you?” at least once a month and even more when I travel. I try to handle the inquiries with as much grace as I can muster. Rather approaching it from an educational perspective and not reactively flying off the handle. Not like the last time, when a few years back, a friend and I were sitting at the bar of our local Colorado hangout, and I was approached by a stranger.

While enjoying my apple whiskey and ginger ale, I felt that spine-tingling feeling you get when someone is looking at you. I looked around, trying to decipher where the feeling was coming from when I noticed a booth with two couples, probably in their mid to late 20s, pointing at me and whispering.

I leaned toward my friend, “Am I crazy, or are those people staring at me?”

She followed my finger that was strategically placed under my chin and pointed in their general direction, “Oh, yeah. Do you know them?”

“Nope,” and I took a swig of my drink, fully prepared to ignore them.

A few minutes later, I felt a tap on my right shoulder. One of the men from the group was now standing between me and my friend's bar stools. He was wearing a black baseball cap that revealed long reddish-brown strands of hair that shaggily curled below his ears and draped around his neck. And he was wearing one of those old Budweiser T-shirts with the frogs that everyone over-quoted in the late 90s.

“Excuse me…” he began. “My friends and I have been staring at you and we’re wondering, what are you?”

“I’m sorry…?” I felt my blood starting to boil, “What do you mean, what am I?”

“You know, like what are you? We can’t figure it out.”

I felt my neck snap back into the base of my skull, creating an unattractive triple chin effect. “I’m human,” I quickly fired back.

The man's face dropped, and I could sense his sudden discomfort. For a moment, I let him linger there like a skydiver who just realized his chute wasn’t working, just so he could understand how it felt to be caught off guard.

I continued, “I’m lots of things but I don’t think that matters, and quite frankly, I find your question rude. Do you want me to interrupt your night by asking you what you are?”

“Uh…uh, sorry.”

He then turned and quickly returned to his table. Minutes later, from the corner of my eye, I watched the group leave the venue and I never saw them again.

I wish that I had been in a better mood or calmer and more empathetic but after a lifetime of such bullshit, you occasionally lose your cool. However, that moment inspired me to sit down and write a powerful poem, “Human,” that was later published in the Fearsome Critters anthology.

During Trump's presidency, the questions momentarily stopped, but it's not because I was accepted but rather because the questions morphed into immediate judgment and hatred. Like, the time my sister and I were at Home Depot buying doors for her new house. While struggling to maneuver them on the large cart, a middle-aged white male who worked there, began clapping and stomping his feet at us. Yelling, “Ándale!” loudly down the corridor. We were in absolute shock. Or the moments I was told to “go back to my country.” Often, I would experience micro-transgressions at the grocery store: strangers approaching me, demanding that I help them, and then arguing with me because I looked like I should work there.

I don’t talk about race or ethnicity with many of my friends. I’m afraid they wouldn’t understand the confusion and question I often feel. We’ve talked a lot about cultural appropriation, especially as it’s become a widely debated topic over the last few years. For me, it feels like a conversation that has excluded a big demographic: those of mixed race and ethnicity. As someone who has never been enough of something, who hasn’t been welcomed into various communities because my skin is not dark enough or I don’t speak the language, can feel more isolating. How can I express a part of myself when I’ve often been excluded for not being enough? Do I have any fight left or the energy to continually prove myself to strangers? That's the infinite question and the internal struggle I can’t resolve.

Often, I wonder, would I feel differently if I hadn’t failed Spanish in High School, or if I had been more eager to learn as a child, or hadn’t been brainwashed by American idealism? My grandma says that “knowing the language doesn’t fix the feeling,” it doesn’t help you feel more connected and maybe she’s right, or maybe it's irrelevant. I’m not sure yet, but what I do know is that there is no welcome parade when you travel to ancestral land. You’re not accepted with open arms or feel an immediate sense of belonging. No one cares if you’ve been hurt or humiliated, or often feel suffocated by racial or ethnic insecurity. You’re one of many. Just another boat trying to navigate the seas of inclusion and self-acceptance.

It ends in your hotel room on a quiet night flipping through the channels, trying to decide between two programs: an American Music Video show or a Spanish telenovela. Instinct said the latter but then your mind conjured up the Madrid saleswoman as if she was standing next to your mattress judging you for not being from here. You turn to the music video channel but just as quickly decide to turn the TV off and finish your pasta outside with the city.

From your hotel balcony, you have the most beautiful view of Barcelona’s City Centre below. A block over, strangers are drinking on the rooftop bar of Casa Batlló. The sunset bounces off their heads and forms a luminous show against Gaudi’s architectural wonder. Suddenly, you feel like a forgotten flame that's been rekindled through the myriad of colors and mosaics. From here, accents cannot be deciphered. Language is no longer an issue.

Over the last nine days, through northbound train rides and city sea walks, you thought a lot about your ancestors. Did they, too, once travel this terrain? Was this where they lived, tucked into Stone Pine hillsides? You wonder, what was it that made them leave this land behind for a new world?

So many questions and so many answers are unknown, but it's here in Barcelona when you realize you’re not a disgrace to your ancestors or some annoying tourist who doesn’t know the language. You are a tiny piece of a communal puzzle, and you know deep down that you will always find your tribe, even if it's not where you expected it to be. And isn’t that the beauty of life: finding out that it's not so much about who has made us but rather what has made us?